SEARCHING FOR SWAN ISLAND

Long Ago and Far Away

copyright 1986 Edwin P. Cutler

spaceship79@hotmail.com

In early 1986 we had sailed half way around the Caribbean, planning to search for the little island with the romantic name Isla de Caine, which means Island of the Swan. We knew the lat and long on the chart as 17N, 83W, and the Swan is nearly two miles long. No problem.

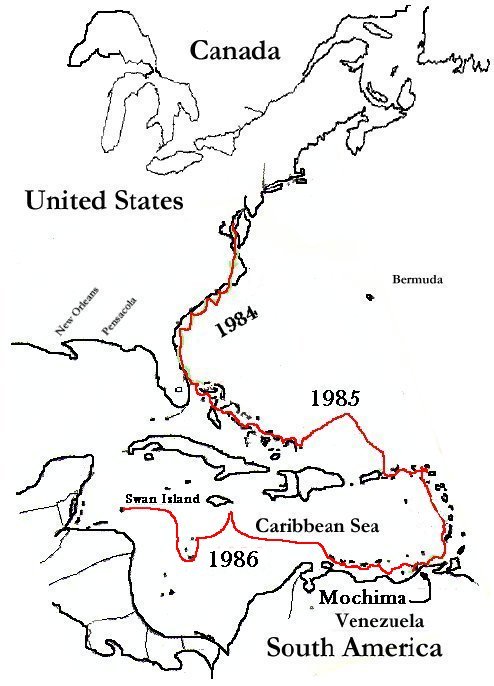

We left Annapolis in Maryland in November of 1984 and sailed down the U.S. coast to Florida. In 1985 we explored the warm Bahamas for several delightful winter months. Back home our friends couldn't believe we were running around in shorts while they shoveled snow. After a sojourn in the Turks and Caicos, we boldly sailed out into the Atlantic and landed in San Juan, Puerto Rico. After taking on fuel and water we realized hurricane season was creeping across our calendar. We wanted to get south of the hurricane belt so headed out into the Caribbean and sailed on a close port tact. We let the Romarin do her thing and ended up in Union Island in the Lesser Antilles. We still needed to be farther south so we worked our way to Grenada and across to Venezuela.

That year the hurricanes all went north of us and we dallied in Venezuela waiting for safe weather. We spent Christmas of 1985 in an inlet where Wendy found the little doll, Mammy.

As you can see on the chart our exploration of the Caribbean was more than a year underway and we were in the south-most loop of the red line on the chart.

Ready to continue our search for the Swan we left Aruba which ships coffee to the United States. They don't raise coffee, it is smuggled into Aruba from Columbia because at the time the U.S. had an economic blockade on Columbia produce. Anchored in Aruba we saw a small freighter loaded with Marlboro cigarettes, all covered with canvas, which were to be used as wampum to buy coffee beans in Columbia.

As we sailed boldly west in 1986, we kept well offshore of Columbia and headed into the western Caribbean islands. Can you imagine heading out into waters where there was no land within several hundred miles of your little old wooden ship.

The chart below shows us coming into the western Caribbean from the east, heading for the Serranilla Banks. Wendy smelled whales, but there were no whales in this part of the Caribbean. We took star shots and discovered the wind or current had carried us far north of our planned course. We worried that the smell could be from the Alice Shoal. Fearing we might run aground, we hauled in our sails and headed south, then turned west again aiming for the Serranilla Bank.

We saw breakers on the Serranilla Bank and anchored in the lee of Beacon Cay. Exhausted we tried to sleep in rolling two foot waves. In the morning a small Colombian Navy boat politely boarded us and asked for our papers. We had trouble with their Spanish until a Jamaican fishing boat came along side and translated for us. All went well.

We didn't want to spend another night rolling around in bed, so we raised anchor and headed south for the Seranna Bank where we found a lonely paradise and spent a week anchored in flat water inside a ring of coral breakers. There was an island which was 18 inches high and 30 feet across, it was like a dream in a blue sky and sea.

Remembering our quest for the Swan we finally headed northwest for the channels which promised deep water on the way to the ridge where the tiny island sits perched on the edge of the Cayman Trench.

It was now May of 1986 and warm Tradewinds filled our tanbark sails and a quartering swell rushed our hull ahead. With searching eyes we looked ahead for the tiny speck that stands out in the northwest Caribbean 180 miles northeast of Roatan Island and 220 miles southwest of the Cayman Islands. One needs a compass to go sailing.

We had been unable to get a detailed chart of Swan Island and the absence of the island in the literature for chartering, diving, and tourism suggested the island may not be inundated with visitors. Just the kind of place we were looking for. We had only Hart and Stone's Cruising Guide which describes the island but has no sketches. Wendy expected to find twenty farmers and some cows. I expected high rises and condominiums

At dusk on the 4th of May 1986 we hove-to and took star shots which put the Swan only 20 miles away to the NNW. The island was three miles wide, a small target but how could we miss it since Hart and Stone promised a 25 mile navigation light?

At nightfall there was a deluge of rain, then a calm, followed by a sprightly N wind at 13mph. We hauled in our sails to make north, but as the sky cleared there was no island in the nighttime shadows, and our little radio heard a TAB Morse code for Tabago which was 600 miles east of us but no promised SWA for Swan Island which the book promised could be heard 50 miles away?

Just after the midnight change of watch the depth sounder began pinging insistently, and Wendy spun the wheel to bring the boat through the wind lest we go frothing onto a steep-to reef. With her bow headed south toward the open sea the Romarin lay hove-to, drifting slowly and safely into deeper water.

We couldn't see an island, but Wendy thought she could smell guano, bird droppings, which long ago had been shipped out of the island for fertilizer. "Why can't we see something this close to Swan Island," I bemoaned the lack of anything that in the dark of night resembled an island. There was no navigation light and even the incorrect TAB Morse code was no longer beeping. We could see the stars quite clearly but worried that we might be blind to all man-made signals.

We decided to remain hove-to until daylight, letting the Romarin work slowly away from the shallow water.

You know it -- we slept through the morning star shots and when we finally woke up there was nothing but water, water everywhere, but no island in sight. A shot at the rising Sun gave us a north-south line of position fifteen miles west of Swan Island, we were downwind and out of sight of such a low island. We had our longitude but our north-south latitude was to elude us for hours.

We set the sails for a close-hauled starboard tack and wore away to the NNE where we hoped to find the bank where the Swan sits and then follow it east to the island.

We tried the radio direction finder again. "A signal!" I shouted to Wendy, but after translating the Morse code, we realized the signal was once again tapping out TAB not SWA."Tobago is a thousand miles away." Wendy wondered aloud.

"And there was no signal at all last night," I added and turned off the radio.

We had enough water, food, and fuel to last well over a month at sea and became determined not to let the little island elude us. As the day progressed we sailed NE then SE, making what turned out to be a big loop.

"Land ho!" At 4:30 in the afternoon, Wendy sighted a wave that would not go away. There, 10 miles over our port bow lay an island to the east. It was just a gossamer line on the hazy horizon, but to us it was Camelot.

Hart and Stone suggest that a bight in the western end of Great Swan gives adequate protection in the prevailing east winds. This small indentation became our goal. Insidiously, the light of day faded as we scanned a little village for signs of activity.

As we approached the island we started the engine and, with a keen eye on the depth sounder, headed for a house we could dimly see on shore.

There were no other boats, and the houses looked strangely deserted. As dusk darkened the day, we dropped our anchor in 18 feet of water well away from a quay and far from a sandy beach, then backed down to bury it in a sandy bottom. We stopped the engine and listened in the silence for sounds of island life. Several white houses sat dark and sinister on a rise of grassy lawn above a little beach.

There were buildings, but the island was ominously dark. We had just begun to relax when a loud shrill whistle screamed from the island shadows. We shivered spastically and looking toward the quay saw a dim lantern light. Looking closer with the binoculars, Wendy made out the forms of three men. The whistle was repeated and the lantern moved from side to side; someone was signaling us.

They called and whistled to us, but gave up at ten o'clock and walked up the quay where their lantern light disappeared amongst the dark houses.

So here we were at Swan Island, with no 25 mile light? And where was the radio beeping SWA?

We were at an island, but there were no boats. There were houses, but there were no lighted windows. There were men on shore, but they appeared to be alone and desperate. Wendy became frightened and feared we might be faced with shipwrecked natives who had lost their boat and were starving on this bleak island. I considered raising the anchor and heading back out to sea -- and safety.

But the with lantern and men out of sight, I decided on anchor watches; if they had no boat they could not attack us in force and we could repel swimming boarders with our mace and flare gun, not to mention wildly wielded machetes in the hands of a frightened crew.

The darkness deepened and the moon-less night surrounded us. The same grey houses, the same shadowy lawns, and the same starlit beach remained deserted. Romarin, blind to the mystery about her, stood at anchor, her twelve tons gently rocking on a somber swell.

The Caribbean had been kind to us, carrying us gently down the windward islands to where, a year after the Marines rescued Grenada from the Cubans, we crossed over to South America. For three months we explored along the coast of Venezuela and lingered amongst the Bahama-like off-shore islands. We had rolled through the Netherlands Antilles on fresh tradewinds that pushed us out past the pirates of Columbia to the banks of the western waters. We had a history of finding pleasant, friendly people; the pirates, robbers, and antagonists had not yet materialized.

But here we were at mysterious Swan Island.

At daybreak the sun began to wake the world. Grey houses were painted white, cows followed their noses in search of dewy grass, the water around us shimmered turquoise over our buried anchor.

Why do the next two pictures not plot right.

Wendy was right, she had guessed cattle grazing and I had guessed high rise buildings.

Beware! Three young men came down to the beach in swim suits and waved to us. We waved back as we ate a leisurely breakfast, cooked on a gimbaled stove.

When they slipped into the warm tropic water and swam toward us, I became concerned.

When the first one, about eighteen, reached the anchor chain I greeted him in Spanish, "Hola."

"My name is Carlos and I speak English." He grinned. "We tried to help you tie up last night." He waved toward the quay. In the light of day our three desperados of last night turned out to be a cook, a sergeant, and a radio operator, all in the Honduras Navy. The island population consisted of one commanding officer, twelve sailors, and one walking cowboy to tend the cattle stationed there.

Our log book recorded:

6 May 1986 8:00 we wake up after a wonderful sleep and have a quiet breakfast.

9:00 three men swim out. Carlos Heinz a radio operator who can speak English, Enrique a cook, and Menoza a sergeant. These men are in the Spanish speaking Honduras Navy and report to Commander Oscar Flores.

When we asked about Nicaragua, which boarders below Honduras, Carlos warned, "The Sandinistas are very bad and will take your boat and everything you have on board if they catch you." The sergeant and the cook grinned and nodded their affirmation. Carlos added with pride, "We are here to protect our Honduras island."

They said a boat from shore brings replacements and supplies each month. The mystery of the missing navigation light was solved when they told us their generator was broken, and the next boat would have parts so they could have lights again tomorrow.

"Tomorrow?" Wendy wondered, remembering that manana doesn't mean tomorrow, it means not today.

With handshakes all around, they invited us to come ashore then dove into the water and swam back to the beach.

We spent the rest of the that bright morning unlashing gear for anchor duty; the search for Swan Island was over. We had found our island and would explore it and meet the people as we had on so many other islands.

After lunch we rowed our dinghy to the clean soft sand beach in front of a tree roofed pavilion which supported a little sign, "No Problem Bar," and I took Wendy's picture.

The United Fruit Company lost 15,000 coconut trees to Hurricane Janet, in 1955, and plantation days on the island came to an end. Shortly after Castro led the revolution in Cuba, the Gibraltar Steamship Company, a CIA front, installed a powerful radio station on Swan Island to broadcast propaganda to Cuba. "Radio Swan" was last used to report the unsuccessful Bay of Pigs invasion during April of 1961. Since then, the U. S. has withdrawn completely from the island, except to provide Honduras with funds to operate a powerful light beacon and a 2.0KW radio beacon to broadcast SWA on 407kHz.

The Honduras Navy had commandeered some of the abandoned buildings of the United Fruit Company and the U.S. weather station. Other buildings, unused for a generation, were surrounded by cows and coconut palms.

Lieutenant Oscar Flores, the base commander greeted us and let us take his photo with Wendy.

We were indeed at a Honduras Naval installation on the islands of the Swan. Actually, there are three islands but the one to the east is very small, has no harbor, and is uninhabited. It may be stretching things to say that the Swan, the one we were on, was inhabited.

Smoke rose from a stone chimney at one end of a summer kitchen, and on the porch of an adjacent building the sergeant who had boarded our boat sat in the shade with several sailors cleaning automatic rifles.

The base commander invited us on a tour. Soon he, Carlos, the sergeant, and the cook, who seemed to be buddies, took us off into the jungle, while nine other men, like boys at summer camp, lifted weights, fished from the quay, swept the kitchen and oiled their automatic guns.

From rocky promontories we saw coral in the surrounding sea. Along a path the sergeant, who said he had a sister in New York, pointed into a tree and enthused, "Guano, guano!"

Guano is bird droppings and we wondered at his bizarre enthusiasm.

We saw lazy lizards, three feet long with serrated dorsal crests, and the mystery was solved. He had been shouting iguana, not guano. We walked through the remains of the coconut groves and watched huge land crabs scurry off amongst unshucked coconuts.

In the surf we picked up snails with one inch diameter feet, but the men indicated they were not good to eat.

We walked past several generations of radio towers some standing forlornly on rusty iron legs and some skeletons lying in repose, embedded in jungle growth.

We found the radio beacon and part of the mystery was solved. It had indeed been repaired just yesterday by a French team who flew in from the mainland. It was powered by solar panels with storage batteries and for some unknown reason blared TAB instead of SWA; it had been the radio tower we had wanted to steer us in and would have been big help if we had not ignored it.

At the end of the tour, the commanding officer made certain that we understood we were invited to lunch the next day. Before we left, the cook wondered if we had any onions on board.

He was delighted when Wendy told him we had some onion powder and promised to bring some in tomorrow.

Then, exhausted, but happy, we walked toward the No Problem Bar and our dinghy. Wendy sighed, "We almost pulled the anchor and fled this lovely island last night."

The next day, in the hay loft of a large barn we found "Radio Swan" -- all three carloads of equipment which had been rerouted from a Voice of America destination in Germany to serve instead in the invasion of Cuba in 1960. However, after only a short ignominious CIA career it had been sentenced, before most of these sailors were born, to languish in this lonely exile. The large radio tubes and switches were beautiful bronze and had not suffered with time.

We found more cattle at the east end of the island and an old narrow gauge railroad that might have been used to haul coconuts to town. There was an orchard in the midst of the buildings left from plantation life.

Twice we had lunch in the summer house with the Honduras Navy. The first time the main course was land crabs in the shell. Their claws were like the claws of Maine lobster, and their bodies opened like Maryland crabs but contained much larger chunks of meat. The second day we had iguana, with a texture and taste much like chicken. Both meals were delicious and filling. What more could you ask for on a deserted island.

One evening, Wendy, content in this lonely outpost wrote in the log, "What a lovely life, to have thirteen young men to cook, carry, tour, find shells, coconuts, and... all as though it was the most wonderful thing they could be doing." We had found Swan Island, at this moment in its history, a pleasant place to visit, a peaceful place to be.

To explore more we sailed our dinghy to the NW side of the island and rolled over the side in our face masks and flippers to discover that we had dropped into a storybook land of coral castles whose lyrical towers reached for the sun from sandy moats twenty feet below the sea. It was a divers paradise.

Back on the island, one of the sailors presented us with a big bag of shucked coconuts, enough to last a month at sea, and the commandant invited us to a building which had a library. The books were all in English, and had been presented by the Scarsdale Women's Club to overseas libraries for service men far from home. He offered us our choice, and we took The Caine Mutiny and From the Terrace.Over a hundred more sit on shelves, a little ways from a broken window, abandoned and unread by these Spanish speaking sailors.

A shout in the yard and word was passed that a ship was coming. Soon FNH 103, a 105 foot PT boat, came into the bight and tied up alongside the quay. On board were a new base commander, and ten new replacements, including a new cook, and a new radio operator. Also, there was a rebuilt armature for the generator and a mechanic to install it.

On May 8, 1986 at lunch on shore the island celebrated Ed's 57th birthday.

A topside tour of the FNH103 revealed a 50 caliber machine gun on the foredeck -- which was too rusty to shoot. Carlos explained that the boat was not very fast since they hit a rock with the original propeller and the only replacement available was a smaller one.

The Honduras Navy had a picnic and jumped and dove off of the visiting boat.

That evening, when stars were appearing in a sky left suddenly dark by a tropical sunset, the generator began to purr and the houses took on a friendly, lived-in look as light poured from their windows. There were only a few yard lights so that even with modernization the aura of the quiet night was not completely dispelled. At the top of the tower the navigation light flashed a bright white beam 25 miles out over the surrounding sea. In the shadow of our cockpit we raised our glasses and toasted technology.

But, at three in the morning, when Wendy got up to check the anchor, she called out from the foredeck, "Oh, dear, all the lights are out again."

"Remember, Carlo said they turn them off at ten o'clock to save fuel."

At dawn, with no navigation light to aid us, we eased out of the little bight and raised sails to reach for our next destiny, the islands of Roatan off the Honduras coast.

When Swan Island sank behind us into the haze, as we had seen it rise over a week ago, TAB for Tobago was still radiating in Morse code on 407kHz from the solar powered radio beacon. We were leaving a land where barefoot sailors feasted on fresh fruit, iguana, escargot, and land crabs but carried lanterns in the night.

We turned our eyes southwest, toward Roatan, knowing that behind us over the curve of the Earth, with palm trees blowing like ruffled feathers in warm tradewinds, Swan Island sits surrounded by soft sand beaches and coral castles, while in the cove, beneath two fathoms of gin clear water, white sand waits for other adventuresome anchors.